Holiday Inn Case Seeds

Two Ideas for Hotel Replacement Cost Cases in Accounting

Bob Jensen

at

Trinity University

One of the most popular Excel

spreadsheets that Bob Jensen ever provided to his students ---

www.cs.trinity.edu/~rjensen/Excel/wtdcase2a.xls

Advantages

and disadvantages of replacement cost (entry value, current cost) accounting are

discussed in greater detail are listed below.

Advantages

of Entry Value (Current Cost, Replacement Cost) Accounting

·

Conforms

to capital maintenance theory that argues in favor of matching current revenues

with what the current costs are of generating those revenues. For example, if

historical cost depreciation is $100 and current cost depreciation is $120,

current cost theory argues that an excess of $20 may be wrongly classified as

profit and distributed as a dividend. When it comes time to replace the asset,

the firm may have mistakenly eaten its seed corn.

·

If the

accurate replacement cost is known and can be matched with current selling

prices, the problems of finding indices for price level adjustments are avoided.

·

Avoids to

some extent booking the spread between selling price and the wholesale "cost" of

an item. Recording a securities “inventory” or any other inventory at exit

values rather than entry values tends to book unrealized sales profits before

they’re actually earned. There may also be considerably variability in exit

values vis-à-vis replacement costs.

Although I

am not in general a current cost (replacement cost, entry-value) advocate, I

think you and Tom are missing the main theory behind the passage of the now

defunct FAS 33 that leaned toward replacement cost valuation as opposed to exit

valuation.

The best

illustration in favor of replacement cost accounting is the infamous Blue Book

used by automobile and truck dealers that lists composite wholesale trading for

each make and model of vehicle in recent years. The Blue Book illustration is

relevant with respect to business equipment currently in use in a company since

virtually all that equipment is now in the “used” category, although most of it

will not have a complete Blue Book per se.

The theory

of Blue Book pricing in accounting is that each used vehicle is unique to a

point that exit valuation in particular instances is very difficult since no two

used vehicles have the same exit value in a particular instances. But the Blue

Book is a market-composite hundreds of dealer transactions of each make and

model in recent months and years on the wholesale market.

Hence I

don’t have any idea about what my 1999 Jeep Cherokee in particular is worth, and

any exit value estimate of my vehicle is pretty much a wild guess relative to

what it most likely would cost me to replace it with another 1999 Jeep Cherokee

from a random sample selection among 2,000 Jeep dealers across the United

States. I merely have to look up the Blue Book price and then estimate what the

dealer charges as a mark up if I want to replace my 1999 Jeep Cherokee.

Since Blue

Book pricing is based upon actual trades that take place, it’s far more reliable

than exit value sticker prices of vehicles in the sales lots.

Conclusion

It is sometimes the replacement market of actual transactions that makes a Blue

Book composite replacement cost more reliable than an exit value estimate of

what I will pay for a particular car from a particular dealer at retail. Of

course this argument is not as crucial to financial assets and liabilities that

are not as unique as a particular used vehicle. Replacement cost valuation for

accounting becomes more defensible for non-financial assets.

Disadvantages of Entry Value (Current Cost, Replacement Cost) Accounting

·

Discovery

of accurate replacement costs is virtually impossible in times of changing

technologies and newer production alternatives. For example, some companies are

using data processing hardware and software that no longer can be purchased or

would never be purchased even if it was available due to changes in technology.

Some companies are using buildings that may not be necessary as production

becomes more outsourced and sales move to the Internet. It is possible to

replace used assets with used assets rather than new assets. Must current costs

rely only upon prices of new assets?

·

Discovering current costs is prohibitively costly if firms have to repeatedly

find current replacement prices on thousands or millions of items.

·

Accurate

derivation of replacement cost is very difficult for items having high

variations in quality. For example, some ten-year old trucks have much higher

used prices than other used trucks of the same type and vintage. Comparisons

with new trucks is very difficult since new trucks have new features, different

expected economic lives, warranties, financing options, and other differences

that make comparisons extremely complex and tedious. In many cases, items are

bought in basket purchases that cover warranties, insurance, buy-back options,

maintenance agreements, etc. Allocating the "cost" to particular components may

be quite arbitrary.

·

Use of

"sector" price indices as surrogates compounds the price-index problem of

general price-level adjustments. For example, if a "transportation" price index

is used to estimate replacement cost, what constitutes a "transportation" price

index? Are such indices available and are they meaningful for the purpose at

hand? When FAS 33 was rescinded in 1986, one of the major reasons was the error

and confusion of using sector indices as surrogates for actual replacement

costs.

·

Current

costs tend to give rise to recognition of holding gains and losses not yet

realized.

Question

What is the difference between "replacement cost" and "factor replacement cost?"

Answer

It is much like a make versus buy decision. As an illustration, the "replacement

cost" of a computer is the price one would pay for a computer in the market to

replace an existing computer. That presumably includes the mark up profits of

vendors in the supply chain. The "factor replacement cost" excludes such mark up

profits to the extent possible by estimating what it would cost in the

"transformation process" to purchase the components for transformation of those

components into a computer. The "factor replacement cost" adds in labor and

manufacturing overhead. It excludes vendor profits in the computer supply chain

but not necessarily vendor profits in the purchase price of components. It

becomes very complicated in practice, however, because computer vendors do such

things as include warranty costs in the pricing of computers. Assembled

computers in house probably have no such warranties. A more detailed account of

factor replacement costing is provided in Chapters 3 and 4 of Edwards and Bell.

Edgar O. Edwards and Philip W. Bell, The Theory and Measurement of Business

Income (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1961).

Of course

this does not solve the fundamental problem of replacement cost accounting that

arises when there are no current assets or component parts of assets that map

directly into older assets still being used by the company. For example, old

computers and parts for those computers are probably no longer available. Newer

computers have many more enhancements that make them virtually impossible to

compare with older computers such using prices of current computers is a huge

stretch when estimating replacement costs of older computers that, for example,

may not even have had the ability to connect to local networks and the Internet.

Zeff

writes as follows on Page 623:

Edwards and Bell, in their provocative volume, propound a measure called

"business profit," which is predicated on what might be termed "factor

replacement cost." "Business profit" is the sum of (1) the excess of current

revenues over the factor replacement cost of that portion of assets that can be

said to have expired currently, and (2) the enhancement during the current

period of the factor replacement cost.

Advantages

and disadvantages of replacement cost (entry value, current cost) accounting are

discussed in greater detail are listed below.

Advantages

of Entry Value (Current Cost, Replacement Cost) Accounting

·

Conforms

to capital maintenance theory that argues in favor of matching current revenues

with what the current costs are of generating those revenues. For example, if

historical cost depreciation is $100 and current cost depreciation is $120,

current cost theory argues that an excess of $20 may be wrongly classified as

profit and distributed as a dividend. When it comes time to replace the asset,

the firm may have mistakenly eaten its seed corn.

·

If the

accurate replacement cost is known and can be matched with current selling

prices, the problems of finding indices for price level adjustments are avoided.

·

Avoids to

some extent booking the spread between selling price and the wholesale "cost" of

an item. Recording a securities “inventory” or any other inventory at exit

values rather than entry values tends to book unrealized sales profits before

they’re actually earned. There may also be considerably variability in exit

values vis-à-vis replacement costs.

Although I

am not in general a current cost (replacement cost, entry-value) advocate, I

think you and Tom are missing the main theory behind the passage of the now

defunct FAS 33 that leaned toward replacement cost valuation as opposed to exit

valuation.

The best

illustration in favor of replacement cost accounting is the infamous Blue Book

used by automobile and truck dealers that lists composite wholesale trading for

each make and model of vehicle in recent years. The Blue Book illustration is

relevant with respect to business equipment currently in use in a company since

virtually all that equipment is now in the “used” category, although most of it

will not have a complete Blue Book per se.

The theory

of Blue Book pricing in accounting is that each used vehicle is unique to a

point that exit valuation in particular instances is very difficult since no two

used vehicles have the same exit value in a particular instances. But the Blue

Book is a market-composite hundreds of dealer transactions of each make and

model in recent months and years on the wholesale market.

Hence I

don’t have any idea about what my 1999 Jeep Cherokee in particular is worth, and

any exit value estimate of my vehicle is pretty much a wild guess relative to

what it most likely would cost me to replace it with another 1999 Jeep Cherokee

from a random sample selection among 2,000 Jeep dealers across the United

States. I merely have to look up the Blue Book price and then estimate what the

dealer charges as a mark up if I want to replace my 1999 Jeep Cherokee.

Since Blue

Book pricing is based upon actual trades that take place, it’s far more reliable

than exit value sticker prices of vehicles in the sales lots.

Conclusion

It is sometimes the replacement market of actual transactions that makes a Blue

Book composite replacement cost more reliable than an exit value estimate of

what I will pay for a particular car from a particular dealer at retail. Of

course this argument is not as crucial to financial assets and liabilities that

are not as unique as a particular used vehicle. Replacement cost valuation for

accounting becomes more defensible for non-financial assets.

The Holiday Inn Case Seeds

Hi Tom,

My recent stay in the Concord Holiday Inn and your replies prompted me to write

an online document called

"Holiday Inn Case Seeds and Questions About Tobin's Q"

Two Ideas for Hotel Replacement Cost Cases in Accounting"

http://www.cs.trinity.edu/~rjensen/temp/HolidayInnCaseSeeds.htm

If you are willing to counter my arguments, I would really like to see

why investors and creditors would be interested in the 2011 Replacement Cost

financial statements for the Concord, NH and Brookline, MA Holiday Inn hotels.

To me it seems that such statements would be more misleading than historical

cost financial statements given the fact that neither historical costs nor

replacement costs are valuation-based financial statements.

Thanks,

Bob

Tom Selling and I have been having a bit of a go around recently

(actually dating back several years) over the benefits of replacement cost

accounting as a substitute of historical cost accounting of operating assets

(land, buildings, machinery, vehicles, etc.).

I have two starting modules on this topic at the following

links:

http://www.trinity.edu/rjensen/Theory02.htm#FairValue (in particular

scroll down to Days Inn and U.S. Steel)

http://www.trinity.edu/rjensen/Theory02.htm#BasesAccounting

Tom has two starting modules on this topic at the following

links:

Click Here and Scroll Down

http://accountingonion.typepad.com/theaccountingonion/2011/12/im-for-auditor-term-limits-but.html

or

Click Here

http://accountingonion.typepad.com/theaccountingonion/2012/01/its-nice-to-win-something-even-if-its-the-losing-cause-man-of-the-year.html

There are three basic issues. One is whether replacement costs

should literally replace historical cost (traditional) accounting of most

operating assets in single-column financial statements. The second issue is

whether replacement cost financial statements should be required as

supplementary financial statements as they were under FAS 33 before it was

rescinded. The third issue and related issue is whether benefits versus costs of

generating verifiable replacement cost numbers are such that the benefits are

deemed much greater or lower than the cost.

The first thing to note is that replacement cost accounting is

not valuation accounting. The current book value of a building after 40 years of

straight line depreciation may be $10 million. The replacement cost may be $120

million today, but the replacement cost book value my only be $40 million after

depreciating the current replacement cost. The exit value of the old building

today be negative since buyers of the site and building only want the land and

would tear down the old building.

The second thing to note is that the cost of generating

verifiable replacement cost numbers for operating assets can be very costly. One

reason is that many of the most expensive assets like factory buildings,

warehouses, stores, hotels, etc. are highly unique. Whereas it's quite easy to

derive the verifiable current replacement cost 500 shares of IBM common shares

because these shares are fungible items, the cost of generating verifiable

replacement cost numbers for each of 500 Holiday Inn hotels is very expensive

since each one varies in location, size, and local construction codes and costs

such as the difference between construction codes and labor costs in Manhattan

versus a hurricane alley in Biloxi.

Today on Friday the 13th (January 13, 2012) Erika and I returned

from staying one night in the Holiday Inn in downtown Concord, NH. and a second

night in the relatively new Marriott Courtyard in Concord.

It dawned on me that it might be informative if some

accounting researcher (not me) wrote a case about two old and rather shabby

Holiday Inn hotels where I've stayed at recently. One might might be described

shabby and possibly uncomfortable. The other might be described as really shabby

and most likely very uncomfortable. I say this noting that I am a Holiday Inn

Priority Club loyalist and frequently seek out Holiday Inn hotels, because they

are usually be best value for the money in terms of location and price. Quality

is variable among Holiday Inns, and location often trumps both price and quality

in some instances, especially the shabby Brookline Holiday Inn that we stay in

frequently that's close to the Harvard Medical School where Erika has repeated

medical services from her wonderful nearby spine surgeon.

Before I describe these two shabby Holiday Inn hotels, I suggest

that these would make wonderful cases for studying how replacement cost

accounting alone can be very misleading. Hence I will concentrate on the

benefits (positive and negative) of replacement cost accounting apart from the

cost of generating verifiable replacement cost data (which would entail input

from (often flakey) real estate appraisers and architects) in the case of

hotels.

Historical Cost Hypothetical Data for the past

year (2011)

Consider first the Holiday Inn in Concord, NH. Based upon my hypothetical data,

the book values 2011 daily revenues and book values are as follows:

$150 plus free parking per night per room average after factoring in an 80%

occupancy rate in 2011

$60 per night net positive cash flow after deducting all cash costs for labor,

utilities, taxes, and daily maintenance of all occupied rooms

$50 per night historical accrual net profit after deducting for room

depreciation (for infrequent new carpets, curtains, paint, mattresses, and

furnishings including TV sets). Since the rooms in this hotel are shabby and

most of the window air conditioners will not allow for varying temperature

settings, I conclude that the rooms are upgraded very, very infrequently in this

particular old hotel).

$50 per night net profit after deducting for building depreciation since this

old building is most likely fully depreciated but still in solid condition.

Replacement Cost Hypothetical Replacement Cost

Data for the past year (2011)

$150 plus free parking per night on average after factoring in an 80% occupancy

rate in 2011

$60 per night net positive cash flow after deducting all cash costs for labor,

utilities, taxes, and daily maintenance of all occupied rooms

$60 per night accrual net profit after deducting for room replacement cost

depreciation (for infrequent new carpets, curtains, paint, mattresses, and

furnishings including TV sets). Since the rooms in this hotel are shabby and

most of the window air conditioners will not allow for varying temperature

settings, I conclude that the rooms are upgraded very, very infrequently in this

particular old hotel).

-$100 per night negative profit per room after deducting building replacement

cost depreciation

Of course the hotel's building was actually replaced, we would

expect room rates to be increased. But since Tom is talking about replacement

costs of historical revenues, it would be pure fiction to adjust replacement

cost financial statements for past earned revenues.

Especially note that 2011 replacement cost financial statements

are not very good estimates of future financial statements since many things

would change if the Concord, NH Holiday Inn building was actually replaced.

Firstly, the 2011 room pricing would most likely be increased as much as

possible to recover the replacement costs and still earn a profit. Secondly,

there would be many innovations such solar panels or other more efficient

attributes of modern building operation and maintenance. In Concord, NH property

taxes would jump enormously for a new building since Concord has the highest

property tax rates in New Hampshire.

It is also uncertain what Tom means by "replacement." In the

case of the Holiday Inn in Concord, NH there are two viable and highly different

"replacement" alternatives. One replacement alternative would be to virtually

gut the lobby, restaurant, and all the rooms but replace everything within the

old building. The other replacement alternative would be to tear down the old

building and replace it with a new and much different building.

What replacement alternative did you

have in mind Tom if you were to generate Year 2011 replacement cost financial

statements for this old Concord, NH Holiday Inn? Should replacement costs be

based upon a gutted old building or an entirely new building?

Now when it comes to the Holiday Inn in Brookline, MA gutting

the old building and putting new rooms in the old building is probably not a

viable option that should be considered. The reason is that this old hotel

building is so poorly designed and wastes so much space that the only viable

replacement alternative would be to build a new building.

My Major Point

My major point is that replacement cost financial statements of the Holiday Inns

in Brookline, MA and Concord, NH are probably more misleading than helpful

if they are not accompanied by general price-level adjusted historical cost

financial statements over the years 2000-2020. The reason is that by Year 2000

the buildings most likely were fully depreciated without any intent to

replace them during those years or in the next decade or more. Replacement

cost adjustments are pure fantasy and probably more misleading than beneficial

until replacement itself is on the table..

The same reasoning applies to aging rooms of Holiday Inns that

are in major airport hotels. Passengers seeking short stays in airport hotels

are most likely not willing to pay $100 more per night for a glitzy room in a

Airport Holiday Inn if the Airport Days Inn hotel across the street is a better

buy for the money and has identical airport shuttle services.

These old buildings with convenient locations are tremendous

cash cows for Holiday Inn or other owners and probably turned out to be better

investments per room than most any other newer Holiday Inn hotels. The reason is

location, location, and location when coupled with price elasticity of room

rates in these particular locations. Each of these Concord, Brookline, and

airport hotels serves a unique type of customer that will not pay $100 more per

night to stay in a nicer room or eat in a nicer restaurant in these particular

locations. The story might well be different for Holiday Inns in downtown

Manhattan, Miami, and San Francisco where customers might willingly pay $100

more per night for a more glitzy room with a view. But who cares about glitz and

the view in downtown Concord or Brookline?

If some case writer is willing to take up my challenge to write

up a case about the Concord, NH Holiday Inn, here are some facts of possible

interest.

1. This Concord Holiday Inn is in a relatively old by solid

building with location, location, location. It's a block from I-93 ramps. It's

on the end of the main downtown street in Concord (downtown is only about four

blocks long). Most importantly it's only a few short blocks from the gold-domed

NH State Capitol building and surrounding state offices and courtrooms.

2. Concord is a very small city/town with relatively poor taxi

service, especially in rush hours. Parking is very tight around the State

Capitol, so there's a huge monopoly advantage of location for the nearby

walking-distant Holiday Inn. Anybody doing business in the State Capitol area

will soon discover this main advantage of the nearby Holiday Inn is that has no

other walking-distance competition If this same Holiday Inn building was

located two miles away it might only be able to charge half as much for its old

shabby rooms. Replacement may then be on the table.

3. One of the huge discomforts of the Concord Holiday Inn is the

window air conditioning. When we checked in to Room 205 in this Concord Holiday

Inn three days ago the air conditioner did not work at all. When we

were moved to Room 206 the air conditioner would only put out a trickle of heat

not suited to the 20F temperature outdoors and a brewing blizzard. When we were

next moved to Room 210 where we had heat for the night but the window air

conditioner only worked on high and was not controllable with a thermostat. So

every two hours during the night I turned the heat on and off so as not to cook

or freeze during the entire night. Since we were not in this hotel for business

at the State Capitol, we moved out to another hotel the next day. Location was

not so important to us, and Holiday Inn really disappointed us in Concord, NH.

Fortunately when we checked in at noon there were some other vacant rooms to try

out for heat. I don't know how the guests managed if they checked in late in the

day and were assigned to rooms with poor heaters.

4. The carpets were so grimy in each of those rooms that we did

not even want our socks to touch the floor.

5. The curtains were so dirty that if you slapped at them you

could literally see the dust fly.

6. Around the bath tub the caulking looked like frayed, cracked,

and mildewed hemp rope.

7. But this hotel was fully occupied as it is on most nights. I

don't think the hotel cared when we checked out a day early. There were people

in line waiting eagerly for our old shabby room. They most likely had business

in downtown Concord or in the State Capitol area.

8. If I had millions of dollars and wanted to buy a profitable

cash cow hotel, I would probably first consider the old Concord Holiday Inn even

if the 2011 replacement cost financial statements made it look like a horrible

investment.

If some case writer is willing to take up my challenge to write

up a case about the Brookline Holiday Inn, here are some facts of possible

interest. For all practical purposes Brookline is a nice area of Boston, and

there really is no way of knowing when you drive from Boston into Brookline.

1. This Brookline Holiday Inn is in a relatively old and weird

building with location, location, location. It's within walking distance of some

of the restaurants and shops, but this is not a noted part of Boston for

tourists But more importantly, the Brookline Holiday Inn is undoubtedly the main

hotel serving the nearby Harvard University Medical Center and ten or more major

hospitals, medical service centers, and offices of hundreds of the best

physicians in the United States.

One of the most disappointing things to Erika and me about this

HUMC (Longwood) area is the shortage of hotels. I cannot imagine why other hotel

chains do not build in this medical center area to serve this enormous medical

complex --- except for one possible reason that the Brookline Holiday Inn has

300 reasonably-priced rooms (relative to many Boston-area hotel prices).

2. Boston is a huge city with great taxi service, but the

streets are poorly laid out and traffic jams caused by perpetual street

construction are legendary. Hence, there are serious drawbacks of not staying in

either the Brookline Marriott Courtyard or Holiday Inn in Brookline. The

Marriott Courtyard is a newer glitzy hotel that charges about $130 more per

night with no medical discounts plus $30 for basement parking. The Holiday Inn

has medical discounts plus parking is only $15 per night in the basement. With a

medical discount the room rates are currently around $150 per night (slightly

more in the so-called "tower").

3. I suspect that by now the 300-room Brookline Holiday Inn is

fully depreciated for accounting purposes. It's a weird building today. Around

1950 it was a huge and traditional Holiday Inn Motel that was two stories in a

rectangular shape with an inner outdoor courtyard for a pool and lounge area.

The far end of the motel was nearly a block from the lobby. Then perhaps 50 or

more years ago, a small tower was built over the lobby attached to a brick and

glass shell that now surrounds the old motel. The tower has six stories and

central heating/cooling, but it's so small that it only has one elevator. The

huge "atrium" part of this Holiday Inn is really just the old motel with its

hundreds of clanking (now "indoor") window air conditioners and the old swimming

pool (now inside the big shell.)

4. The carpets are so grimy in each of those rooms that we do

not even want our socks to touch the floor.

5. The curtains are so dirty that if you slap at them you can

literally see the dust fly.

6. Around the bath tub the caulking looks like frayed, cracked,

and mildewed hemp rope.

7. But this hotel is 80% occupied on most nights and fully

occupied on event nights in the Boston area such as Red Sox games and nearby

Boston University graduations and alumni events. The steady customers come in

two varieties. Some are "doing business" with the many nearby hospitals and the

Harvard University Medical Center itself. For example, it's very common to ride

the shuttle van to the hospitals with medical school graduates from all over the

world who are now seeking residency training in this area. The second variety of

Holiday Inn guests are old folks like us with appointments in the hospitals and

many offices of physicians in the area.

8. If I had millions of dollars and wanted to buy a profitable

cash cow hotel, I would probably consider the old Brookline Holiday Inn even if

the 2011 replacement cost financial statements made it look like a horrible

investment.

9. If a hotel chain like Hilton or Sheraton built a towering

hotel in Brookline, the room prices would probably have to be so high that the

Brookline Holiday Inn with its 300 rooms would still thrive because of lower

prices. Guests just do not come to Brookline for the Boston Pops, theatres,

skiing, conventions, or the ocean beaches. The bigger and better hotels are

located closer to downtown Boston.

What I really would like to see is for a diligent case

researcher to dig out the true financial and marketing data for both the Concord

and Brookline Holiday Inn hotels. Case writers usually are skillful about

disguising true hotel names and locations if the owners do not want to be

associated with the case writeups. The Brookline Holiday Inn actually is not

owned by Holiday Inn even though it is a Holiday Inn. About two years ago it was

purchased by new owners who spent quite a lot of money on the lobby area and

putting new carpets in the hallways. Not much has changed in the rooms as far as

I can tell.

The new owners have not yet been able to make the restaurant

pay. It is huge and closed every noon and night. Guests can eat hamburgers and

finger foods in the bar, but the bar is never busy since old folks going to

hospitals are not good bar customers. These folks are most apt to eat in the

excellent hospital cafeterias before returning to their hotel. The bar has one

bartender and no table servers other than the bar tender.

I don't know anything about the Concord Holiday Inn ownership.

If I were CEO of Holiday Inn I would want the particular Holiday

Inns in Concord and Brookline upgraded to at least what one expects in the way

of cleanliness, appearance, and air conditioning in any Holiday Inn hotel.

But I would not expect much since these hotels are cash cows without having to

invest a whole lot more in plant.

My Main Concluding Point

My major point is that replacement cost financial statements of the Holiday Inns

in Brookline, MA and Concord, NH are probably more misleading than helpful if

they are not accompanied by general price-level adjusted historical cost

financial statements over the years 2000-2020. Replacement cost accounting

statements would've made the 2011 financial performances of these hotels look

too gloomy. The main reason is that thus far in the 21st Century the

buildings most likely are fully depreciated without any intent to replace them

in decades to come. Replacement cost adjustments are pure fantasy and probably

more misleading than beneficial until replacement itself is on the table. Why

should replacement be on the table since these fully depreciated buildings

remain such huge cash cows in markets that are very price elastic?

These old buildings with convenient locations are tremendous

cash cows for Holiday Inn owners and probably turned out to be better

investments per room than most any other newer Holiday Inn hotels. The reason is

location, location, and location when coupled with price elasticity of room

rates in these particular locations. Each of these Concord, Brookline, and

airport hotels serves a unique type of customer that will not pay $100 more per

night to stay in a nicer room or eat in a nicer restaurant in these particular

locations. The story might well be different for Holiday Inns in downtown

Manhattan, Miami, and San Francisco where customers might willingly pay $100

more per night for a more glitzy room with a view. But who cares about glitz and

the view in downtown Concord or Brookline?

The aging Holiday Inn hotels in Concord, NH and Brookline, MA

have not been replaced in the 21st century and most likely will not be replaced

tor 20 or more years even though rooms will be refurbished on some cycle like

every 10 years. Rates will remain relatively high for these old hotel rooms and

yearly occupancy will remain high. However, the rates are not so high as to

attract bigger and more expensive hotels to be built on nearby sites. This is in

large part due to the price competition of these older Holiday Inns that will

attract a particular type of clientele that is more price conscious than

vacationers in Manhattan, Biloxi, or San Francisco.

Replacement Cost accounting may be more suited to a Holiday Inn

on Miami Beach than it is for downtown Concord, NH or Brookline, MA.

January 14, 2012 reply from Tom Selling

Bob,

I am actually in the middle of writing a replacement cost-themed blog post,

which I hope to have completed by Monday at the latest. I think this will

answer some of your questions. As to the question of how replacement cost

numbers would be used by investors, I do have three quick responses:

·

Replacement costs are an input to the calculation of Tobin’s Q, which is a

tool used by financial analysts – even though the accounting data available

is a very unreliable surrogate for replacement costs.

·

Replacement costs measure the amount of wealth invested in assets, and form

the foundation for determining what an adequate return on investment should

be. With historic cost accounting, one doesn’t have a clue as to the amount

of wealth invested for which a return is to be expected.

·

This is undeveloped at this point, but I may soon be writing a blog post on

replacement costs and LBOs. The motivation is in large part due to the

criticisms (justified or not) of how Romney made his fortune. When Mitt

Romney is being criticized for being a “vulture”, the public doesn’t realize

that at least part of the motivation for an LBO transaction in which the

company is taken private is the available accounting treatment. One

important factor is that the acquirer may be able to avoid recording a new

basis for the assets “acquired” in the LBO. As a result, the going public

prospectus will understate depreciation and show inflated measures of

profitability and ROA. Assuming for the moment that this was the only basis

for the transaction, then LBO activity is obviously inefficient to society

as a whole – even though Bain Capital may have generated a high return for

itself by “churning” the company – and wreaking havoc in the process.

Again, this is an undeveloped point.

Finally, I will give you an example similar to your hotels, but more

personal and one that my wife and I was just talking about today. We have a

condo in Hanover NH that we rent to Dartmouth students. It has been rented

100% of the time, and we increase the rent each year like clockwork. In

short, it’s a cash cow. I purchased it 25 years ago, so its book value is

close to zero. Also, because of its age and some other unique factors we

couldn’t sell it for anywhere near the present value of the future expected

cash flows – even though I might like to sell it at this point in our lives.

How would I measure this condo on our personal balance sheet? I would say

that the most appropriate way would be to determine how much it would cost

me to replace the expected future cash flows. But, I AGREE WITH YOU that

this would be very subjective and perhaps even costly to undertake. As an

accounting policy, in such a case, I believe the utility of the condo might

be reasonably (although pretty conservatively) measured by the amount we

could sell it for. Although not identical, this is pretty consistent with

the “ceiling” limitation on the ARB 43 “market” measurement for inventories,

which has stood the test of time (60 years, maybe) better than any other

accounting standard I can think of.

In the case of your hotels, I would add that there are plenty of brokers

that list all sorts of run down properties similar to the hotels you stayed

at. Location may be important to you, but to investors, it’s the cash flows

that really count. I suppose that location may be unique for some small set

of assets that are highly integrated with other assets, but that’s more a

question of the unit of account – which is a problem no matter which basis

of measurement one uses.

By the way, Bob, I’m writing this from your old stomping grounds – San

Antonio. We’re here to watch our son play basketball for Trinity U – and

I’ll be meeting Walter Schuetze for lunch tomorrow.

January 14, 2012 reply from Bob Jensen

Hi Tom,

The real problem is that 2011 replacement costs financial statements are

mixing 2011 realized revenues with future replacement investments that,

among other things, will have future incremental revenues not factored into

realized 2011 revenues. These are not 2011 proforma statements using

forecast revenues from replacement assets. These are 2011 realized revenues

generated from the old operating assets.

You're still missing my point about replacement cost 2011 financial

statements for the Concord Holiday Inn. Mixing 2011 earned revenues with the

depreciated cost of a new hotel that's not even being contemplated seems to

me to be a bad case of mixing realized revenues with a totally fictional

building investment.

I just don't see how 2011 replacement cost financial statements would be

be of great interest to investors in shares of this hotel's ownership. The

investors might be interested in pro forma statements based upon future cash

flow streams for various alternative new hotel replacements, but this is not

the same as 2011 replacement cost financial statements on the old hotel

building.

As far as Tobin's Q goes for Holiday Inns, it would be interesting to see

if analysts have ever tried to use this ratio for evaluating past

performance of hotels. My guess is that it would be very hard to find a

hotel investment analyst who puts much stock in Tobin's Q. Hotel analysts

will look to past traditional financial statements of a hotel to see how

well management of that hotel managed past invested capital and will

estimate future cash flow streams under various configurations of new

investments, new management, and shifts in market conditions (such as new

hotel construction by competitors in the vicinity).

But I am impressed that you are indeed attempting to show both me and

hotel investment analysts how they've been missing the boat by not using

Tobin's Q. There might be great consulting opportunities for you here if you

can show them how Tobin's Q can benefit them more than the traditional ways

they evaluate past performance of a hotel and future prospects for that

hotel if it is replaced.

The real problem as I see it is that future replacement costs need to be

matched with estimated future revenues. That makes sense, but matching past

revenues with future investments makes little sense and is limited to the

extent that past revenues are predictive of future revenues. In the case of

hotel replacement, however, hotel pricing is likely to change in order cover

new invested money.

My Major Point A new hotel might also attract new types revenues. For

example, neither the Concord Holiday Inn nor Brookline Holiday Inn hotel

makes much money from their lousy and tiny meeting rooms. Replacement hotels

might contain better meeting rooms that attract mini-conferences and local

events. This reinforces my contention that future replacements need to be

matched with future revenues rather than past realized revenues. This could

complicate Tobin's Q analysis since current revenues in the numerator do not

contain incremental new meeting room revenues of the future if the

replacements are actually made in the future.

But I'm really looking forward to a Tobin Q analysis of the Holiday Inns

in Concord and Brookline where there seems to be little incentive to replace

highly successful older hotels rolling in the cash.

One possible research project might be to interview and or survey

financial analysts in general to see why and how they use in Tobin's Q. You

may be assuming too much about the value of Tobin's Q in portfolio decision

making.

One added note Tom.

An alternative definition of Tobin's Q is as follows:

Definition of 'Q Ratio (Tobin's Q Ratio)'

A ratio devised by James Tobin of Yale University,

Nobel laureate in economics, who hypothesized that the combined market

value of all the companies on

the

stock

market should be about equal to their

replacement costs. The Q ratio is calculated as the market value of

a company divided by the replacement value of the firm's assets:

To me this is a very troublesome definition. Besides the usual problems

of measuring the value of the firm (the numerator) in practice, there's the

issue of that that value is affected by virtually everything in the world

concerning a firm, including such factors as changes in competition, changes

in the supply chain, changes in national and world events, etc.

And the there's the intractable problem of computing the replacement cost

of the "firm's assets" in the denominator. One huge stumbling block is that

accountants usually partition "assets" into those that are booked versus

those that are unbooked in the ledger. Unbooked assets include many

intangibles such as the value of the firm's human resources, the value of

its trademarks and reputation, and on and on and on. How do we compute the

replacement value of the human resources and reputation of Apple

Corporation?

Certainly scholars in the accounting academy who have written about

replacement cost accounting never envisioned the components of Tobin's Q.

Virtually all those scholars limited the scope of replacement cost

accounting to converting booked historical cost (or possibly exit values) of

booked assets into replacement costs. Thus, previous replacement cost

accounting scholars really have not, to my knowledge, written anything

practical about adding the other components to Tobin's Q.

I suggest that you, Tom, confine your analysis of replacement cost

accounting to only comparisons of traditional versus replacement cost

financial statements containing only items booked in the ledger. I is

entirely impractical to suggest deriving replacement costs of all of a

firm's unbooked assets.

Thanks,

Bob

January 17, 2012 Update

Tom Selling has what I consider to be a much more reasonable posting on

replacement costing:

"What I Mean by "Replacement Cost" is not Literally Replacement Cost," by

Tom Selling, The Accounting Onion, January 17, 2012 ---

Click Here

http://accountingonion.typepad.com/theaccountingonion/2012/01/what-i-mean-by-replacement-cost-is-not-literally-replacement-cost.html?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+typepad%2Ftheaccountingonion+%28The+Accounting+Onion%29

Jensen Comment

His latest posting remains, however, disappointing to me in that he does not

delve into how traditional replacement (current) cost accounting of operating

assets like factories, stores, hotels, airliners, can be more misleading than

helpful if it is not accompanied by traditional historical cost financial

statements and possibly exit value statements (although exit value is not very

relevant for going concerns with lots of synergy covariances of asset values "in

use."

Some of his statements do not adequately stress that replacement cost

accounting is not value accounting since it has identical accrual issues of

depreciation, depletion, amortization, bad debt estimation, etc. that plagues

historical cost accounting. For example, he states:

"First, replacement cost measures are the only

possible way for accounting to reflect wealth invested by shareholders in an

enterprise; and consequently, changes in invested wealth."

Tom Selling as cited

above

Firstly, I almost always advise against sweeping generalization such as the

"only possible way to reflect wealth invested by shareholders ..."

Such sweeping generalizations should be avoided in the Academy, especially when

when our accounting history research literature is brimming articles from

scholars who do not share Tom's view about replacement cost accounting (even in

theory). Kenneth McNeal would not call replacement cost accounting "Truth in

Accounting" or even being the best of asset measurement alternatives ---

http://www.trinity.edu/rjensen/Theory02.htm#BasesAccounting

Secondly, he still is speaking of "flowers in spring" to Julie Andrews

without giving her the "show me" she's demanding. He still has not made a

convincing case on how even his hybrid version of replacement cost accounting

would be relevant to my two Holiday Inn case seeds at

http://www.cs.trinity.edu/~rjensen/temp/HolidayInnCaseSeeds.htm

To his credit, in his latest posting Tom does not mention Tobin's Q. Perhaps

I convinced him that Tobin's Q is just not relevant to this analysis since the

value of a firm is affected by so many factors other than items accountants book

into the ledgers. I discuss this problem with Tobin's Q at

http://www.cs.trinity.edu/~rjensen/temp/HolidayInnCaseSeeds.htm

In any case I hope Tom will continue our debate on replacement costs. My

challenge to him remains to take my two Holiday Inn case seeds and show how

replacement cost measures "are the only possible way

for accounting to reflect wealth invested by shareholders in an enterprise; and

consequently, changes in invested wealth" in these two hotels.

http://www.cs.trinity.edu/~rjensen/temp/HolidayInnCaseSeeds.htm

February 7, 2013 Update

From PwC on February 5, 2013

Reporting of Amounts Reclassified Out of Accumulated Other Comprehensive

Income

On February 5, 2013, the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) issued

Accounting Standards Update No. 2013-02, Reporting of Amounts Reclassified Out

of Accumulated Other Comprehensive Income. This guidance is the culmination of

the board's redeliberation on reporting reclassification adjustments from

accumulated other comprehensive income. The new requirements will take effect

for public companies in interim and annual reporting periods beginning after

December 15, 2012 (the first quarter of 2013 for public, calendar-year

companies).

http://www.pwc.com/en_US/us/cfodirect/assets/pdf/in-brief/in-brief-2013-05-fasb-other-comprehensive-income.pdf

Question

If the media insists on reporting one earnings number, which of the alternative

earnings numbers should be reported?

In particular, should net earnings be reported before or after remeasuring

financial instruments for unrealized changes in fair value?

Hint

The following paper has a great summary of the history of OCI and problems

facing the FASB and IASB as we look to the future of financial reporting of

business firms.

"Academic Research and Standard-Setting: The Case of Other Comprehensive

Income," by Lynn L. Rees and Philip B. Shane, Accounting Horizons,

December 2012, Vol. 26, No. 4, pp. 789-815. ---

http://aaajournals.org/doi/full/10.2308/acch-50237

This paper links academic accounting research on

comprehensive income reporting with the accounting standard-setting efforts

of the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) and the International

Accounting Standards Board (IASB). We begin by discussing the development of

reporting other comprehensive income, and we identify a significant weakness

in the FASB's Conceptual Framework, in the lack of a cohesive definition of

any subcategory of comprehensive income, including earnings. We identify

several attributes that could help allocate comprehensive income between net

income, other comprehensive income, and other subcategories. We then review

academic research related to remaining standard-setting issues, and identify

gaps in academic research where hypotheses could be developed and tested.

Our objectives are to (1) stimulate standard-setters to better conceptualize

what is meant by other comprehensive income and to distinguish it from

earnings, and (2) stimulate researchers to develop and test hypotheses that

might help in that process.

. . .

Potential Alternative Definitions of Earnings

Table 1 summarizes and categorizes various

standard-setting issues related to reporting comprehensive income, and

provides the organizing structure for our literature review later in the

paper. The most important of these issues is the definition of earnings, or

what makes up earnings and how it is distinguished from OCI. This is a

“cross-cutting” issue because it arises when the Boards deliberate on

various topics. The Boards cooperatively initiated the financial statement

presentation project intending, in part, to solve the comprehensive income

composition problem, but the project was subsequently delayed.

Table 2 presents a list of the specific

comprehensive income components under current U.S. GAAP that require

recognition as OCI. The second column presents the statement that provided

financial reporting guidance for the OCI component, along with its effective

date. The effective dates provide an indication as to how the OCI components

have expanded over time. Since the issuance of Statement No. 130, which

established formal reporting of OCI, new OCI-expanding requirements were

promulgated in Statement No. 133. Financial instruments, insurance, and

leases are three examples of topics currently on the FASB's agenda where OCI

has been discussed as an option to report various gains and losses. In all

these discussions, a framework is lacking that can guide standard-setter

decisions. The increased use of accumulated OCI to capture various changes

in net assets and the likely expansion of OCI items reinforce the notion

that standard-setters must eventually come to grips with the distinction

between OCI and earnings, or even whether the practice of reporting OCI with

recycling should be retained.7

Presumably, elements with similar informational

attributes should be classified together in financial statements. It is

unclear what attributes the items listed in Table 2 possess that result in

their being characterized differently from other components of income.

Notably, the basis for conclusions of the FASB standards gives little to no

economic reasoning for the decision to place these items in OCI. While not

exhaustive, Table 2 presents four attributes that standard-setters could

potentially use to distinguish between earnings and OCI: (1) the degree of

persistence of the item, (2) whether the item results from a firm's core

operations, (3) whether the item represents a change in net assets that is

reasonably within management's control, and (4) whether the item results

from remeasurement of an asset/liability. We discuss in turn the merits and

potential problems of using these attributes to form a reporting framework

for comprehensive income.

Degree of Persistence.

The degree of persistence of various comprehensive

income components has significant implications for firm value (e.g.,

Friedman 1957; Kormendi and Lipe 1987; Collins and Kothari 1989). Ohlson's

(1995, 1999) valuation model places a heavy emphasis on earnings

persistence, which suggests that a reporting format that facilitates

identifying the level of persistence across income components could be

useful to investors. Examples abound as to how the concept of income

persistence has been used in standard-setting, including separate

presentation in the income statement for one-time items, extraordinary

items, and discontinued operations. Standard-setters have justified several

footnote disclosures (segmental disclosures) and disaggregation requirements

(e.g., components of pension expense) on the basis of providing information

to financial statement users about the persistence of various income

statement components.

Thus, the persistence of revenue and expense items

potentially could serve as a distinguishing characteristic of earnings and

OCI. Table 2 shows that we regard all the items currently recognized in OCI

as having relatively low persistence. However, several other low-persistence

items are not recognized in OCI; for example, gains/losses on sale of

assets, impairments of assets, restructuring charges, and gains/losses from

litigation. To be consistent with this definition of OCI, the current

paradigm must change significantly, and the resulting total for OCI would

look substantially different from what it is now.

Using persistence of an item to distinguish

earnings from OCI would create significant problems for standard-setters.

Persistence can range from completely transitory (zero persistence) to

permanent (100 percent persistence). At what point along this range is an

item persistent enough to be recorded in earnings? While restructuring

charges are typically considered as having low persistence, if they occur

every two to three years, is this frequent enough to be classified with

other earnings components or infrequent enough to be classified with OCI?

Furthermore, the relative persistence of an item likely varies across

industries, and even across firms.

In spite of these inherent difficulties,

standard-setters could establish criteria related to persistence that they

might use to ultimately determine the classification of particular items. In

addition, standard-setters would not be restricted to classifying income

components in one of two categories. As an example, highly persistent

components could be classified as part of “recurring earnings,”

medium-persistence items could go to “other earnings,” and low-persistence

items to OCI (or some other nomenclature). Standard-setters could create

additional partitions as needed.

Core Operations.

Classifying income components as earnings or OCI

based on whether they are part of a firm's core operations is intuitively

appealing. This criterion is related to income persistence, as we would

expect core earnings to be more persistent than noncore income items.

Furthermore, classifying income based on whether it is part of core

operations has a long history in accounting.

In current practice, companies and investors place

primary importance on some variant of earnings. However, it is not clear

which variant of earnings is superior. Many companies report pro forma net

income, which presumably provides investors with a more representative

measure of the company's core income, but definitions of pro forma earnings

vary across firms. Similarly, analysts tend to forecast a company's core

earnings (Gu and Chen 2004). Evidence in prior research indicates that pro

forma earnings and actual earnings forecasted by analysts are more closely

associated with share prices than income from continuing operations based on

current U.S. GAAP (e.g., Bradshaw and Sloan 2002; Bhattacharya et al. 2003).

The problems inherent with this attribute are

similar to those of the earnings-persistence criterion. No generally

accepted definition of core operations exists. At what point along a

continuum does an activity become part of the core operations of a business?

As Table 2 indicates, classifying gains/losses from holding

available-for-sale securities as part of core earnings depends on whether

the firm operates in the financial sector. Different operating environments

across firms and industries could make it difficult for standard-setters to

determine whether an item belongs in core earnings or OCI.8 In addition,

differences in application across firms may give rise to concerns about

comparability and potential for abuse on the part of managers in exercising

their discretion (e.g., Barth et al. 2011).

The FASB's (2010) Staff Draft on Financial

Statement Presentation tries to address the definitional issue by using

interrelationships and synergies between assets and liabilities as a

criterion to distinguish operating (or core) activities from investing (or

noncore) activities. Specifically, the Staff Draft states:

An entity shall classify in the operating category:

Assets that are used as part of the entity's

day-to-day business and all changes in those assets Liabilities that arise

from the entity's day-to-day business and all changes in those liabilities.

Operating activities generate revenue through a

process that requires the interrelated use of the entity's resources. An

asset or a liability that an entity uses to generate a return and any change

in that asset or liability shall be classified in the investing category. No

significant synergies are created for the entity by combining an asset or a

liability classified in the investing category with other resources of the

entity. An asset or a liability classified in the investing category may

yield a return for the entity in the form of, for example, interest,

dividends, royalties, equity income, gains, or losses. (FASB 2010, paras.

72, 73, 81)

The above distinction between operating activities

and investing activities could similarly be used to distinguish between core

activities and noncore activities. Alternatively, standard-setters might

develop other definitions. Similar to the degree of persistence attribute,

standard-setters would not be restricted to a simple core versus noncore

dichotomy when using this definition.

Another possible solution is to allow management to

determine which items belong in core earnings. Companies exercise this

discretion today when they choose to disclose pro forma earnings.

Furthermore, the FASB established the precedent of the “management approach”

when it allowed management to determine how to report segment disclosures.

In several other areas of U.S. GAAP, management is responsible for

establishing boundaries that define its operating environment. FASB

Accounting Standards Codification Topic 320 (formerly Statement 115) permits

different measurements for identical investments based on management's

intent to sell or hold the instrument. Other examples where U.S. GAAP allows

for management discretion include determining the rate to discount pension

liabilities, defining reporting units, and determining whether an impairment

is other than temporary. However, the management approach accentuates the

concern about comparability and potential for abuse.

Management Control.

Given a premise that evaluating management's

stewardship is a primary role of financial statements, a possible rationale

for excluding certain items from earnings is that they do not provide a good

measure to evaluate management.9 Management can largely control the firm's

operating costs and can influence the level of revenues generated. However,

some decisions that affect comprehensive income can be established by

company policy or the company mission statement and, thus, be outside the

control of management. For example, a company policy might be to invest

excess cash in marketable securities with the objective of maximizing

returns. Once the board of directors establishes this policy, management has

little influence over how market-wide fluctuations in security prices affect

earnings, and hedging the gains/losses would be inconsistent with the

objective of maximizing returns. Similarly, a company's mission statement

might include expansion overseas, or prior management might have already

decided to establish a foreign subsidiary. The resulting gains/losses from

foreign currency fluctuations would seemingly be out of management's

control, and hedging these gains/losses would not make economic sense if the

subsidiary's functional currency is its local currency and the parent has no

intention of repatriating the subsidiary's cash flows.

Of course, determining what is and is not

ostensibly under management's control becomes highly subjective and would

probably differ across industries, and perhaps even across firms within

industries. For example, gains/losses from investment holdings might not be

relevant in evaluating management of some companies, but might be very

relevant for managers of holding companies. In addition, the time horizon

affects what is under management's control. That is, as the time horizon

lengthens, more things are under management's control.

In Table 2, we classify items as not under

management's control if they are based on fluctuations in stock prices or

exchange rates, which academic research shows to be largely random within

efficient markets. Using this classification model, most, but not all, of

the OCI items listed in Table 2 are classified as not under the management's

control. Some of the pension items currently recognized in OCI are within

the control of management, because management controls the decision to

revise a pension plan. While management has control over when to harvest

gains/losses on available-for-sale (AFS) securities by deciding when to sell

the securities, it cannot control market prices. Thus, under this criterion,

unrealized gains/losses on AFS securities are appropriately recognized in

OCI. However, gains/losses on trading securities and the effects of tax rate

changes are beyond management's control, and yet, these items are currently

included as part of earnings. Thus, “management control” does not

distinguish what is and is not included in earnings under current U.S. GAAP.

Remeasurements.

Barker (2004) explains how the measurement and

presentation of comprehensive income might rely on remeasurements. The

FASB's (2010) Staff Draft on Financial Statement Presentation defines

remeasurements as follows:

A remeasurement is an amount recognized in

comprehensive income that increases or decreases the net carrying amount of

an asset or a liability and that is the result of:

A change in (or realization of) a current price or

value A change in an estimate of a current price or value or A change in any

estimate or method used to measure the carrying amount of an asset or a

liability. (FASB 2010, para. 234)

Using this definition, examples of remeasurements

are impairments of land, unrealized gains/losses due to fair value changes

in securities, income tax expenses due to changes in statutory tax rates,

and unexpected gains/losses from holding pension assets. All of these items

represent a change in carrying value of an already existing asset or

liability due to changes in prices or estimates (land, investments, deferred

tax asset/liability, and pension asset/liability, respectively).

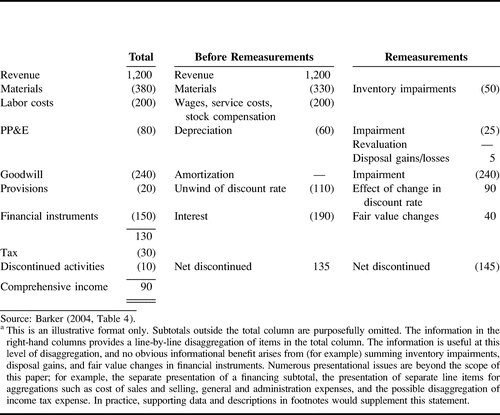

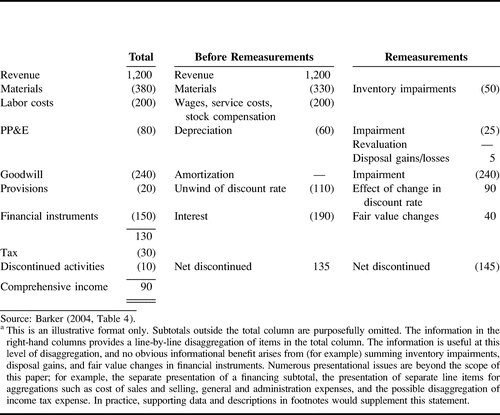

Table 3 reproduces a table from Barker (2004) that

illustrates how a firm's income statement might look using a “matrix format”

if standard-setters adopt the remeasurement approach to reporting

comprehensive income. Note that the presentation in Table 3 does not employ

earnings as a subtotal of comprehensive income; however, the approach could

be modified to define earnings as the sum of all items before remeasurements,

if considered useful. Tarca et al. (2008) conduct an experiment with

analysts, accountants, and M.B.A. students to assess whether the matrix

income statement format in Table 3 facilitates or hinders users' ability to

extract information. They find evidence suggesting that the matrix format

facilitates more accurate information extraction for users across all

sophistication levels relative to a typical format based on IAS 1.

Table 3: Illustration of Matrix Reporting Format

Employing remeasurements to distinguish between

earnings and other comprehensive income largely incorporates the criterion

of earnings persistence. Most remeasurements result from price changes,

where the current change has little or no association with future changes

and, therefore, these components of income are transitory. In contrast,

earnings components before remeasurements generally represent items that are

likely more persistent.

Perhaps the most significant advantage of the

remeasurement criterion is that it is less subjective than the other

criteria previously discussed. Most of the other criteria in Table 2 are

continuous in nature. Drawing a bright line to differentiate what belongs in

earnings from what belongs in OCI is challenging and will likely be

susceptible to income manipulation. In contrast, determining whether a

component of income arises from a remeasurement is more straightforward.

Yet another advantage of this approach is it allows

for a full fair value balance sheet that clearly discloses the effects of

fair value measurement on periodic comprehensive income, while also showing

earnings effects under a modified historical cost system (i.e., before

remeasurements). This approach could potentially provide better information

about probable future cash flows.

Other.

The attributes standard-setters could use to

classify income components into earnings or OCI are not limited to the list

in Table 2. Ketz (1999) suggests using the level of measurement uncertainty.

As an example, gains/losses from Level 1 fair value measurements might be

viewed as sufficiently certain to include in earnings, while Level 3 fair

value measurements might generate gains/losses that belong in OCI. Song et

al. (2010) provide some support for this partition in that they document the

value relevance of Level 1 and Level 2 fair values exceeds the value

relevance of Level 3 fair values.

Another potential attribute might be the horizon

over which unrealized gains/losses are ultimately realized. That is,

unrealized gains/losses from foreign currency fluctuations, term life

insurance contracts, or holding pension assets that will not be realized for

many years in the future might be disclosed as part of OCI, whereas

unrealized gains/losses from trading and available-for-sale securities could

be part of earnings.

As previously discussed, the attributes of

measurement uncertainty and timeliness create similar problems in

determining where to draw the line. Which items are sufficiently reliable

(or timely) to include in earnings, and will differences in implementation

across firms and industries impair comparability?

The overriding purpose of the discussion in this

subsection is to point out that several alternative attributes could

potentially guide standard-setters in establishing criteria to differentiate

earnings from OCI. Ultimately, the choice regarding whether/how to

distinguish net income from OCI is a matter of policy. However, academic

research can inform policy decisions, as described in the fourth and fifth

sections.

Summary

Reporting OCI is a relatively recent phenomenon

that presumes financial statement users are provided with better information

when specific comprehensive income components are excluded from

earnings-per-share (EPS), and recycled back into net income only after the

occurrence of a specified transaction or event. The number of income

components included in OCI has increased over time, and this expansion is

likely to continue as standard-setters address new agenda items (e.g.,

financial instruments and insurance contracts). The lack of a clear

definitional distinction between earnings and OCI in the FASB/IASB

Conceptual Frameworks has led to: (1) ad hoc decisions on the income

components classified in OCI, and (2) no conceptual basis for deciding

whether OCI should be excluded from earnings-per-share (EPS) in the current

period or recycled through EPS in subsequent periods. In this section, we

discussed alternative criteria that standard-setters could use to

distinguish earnings from OCI, along with the advantages and challenges of

each criterion. Further, due to the inherent difficulties in drawing bright

lines between earnings that are persistent versus transitory, core versus

noncore, under management control or not, and amenable to remeasurement or

not, standard-setters might consider eliminating OCI; that is, they might

decide to adopt an all-inclusive income statement approach, where

comprehensive income is reporte

. . .

Continued in article

Jensen Comment

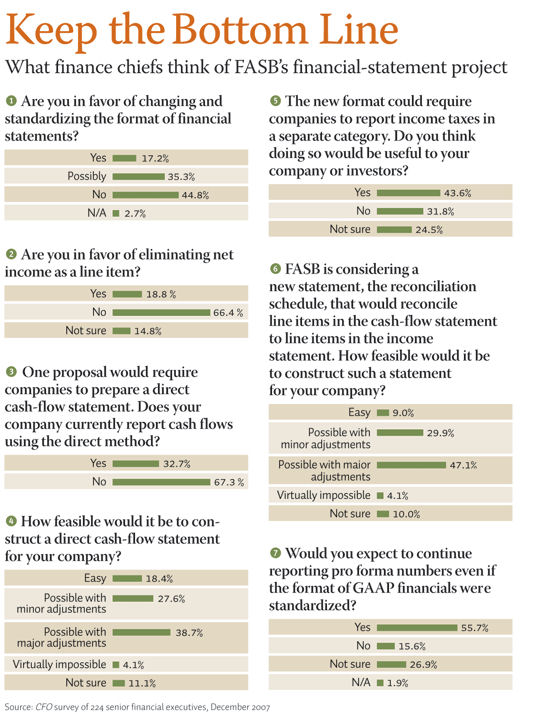

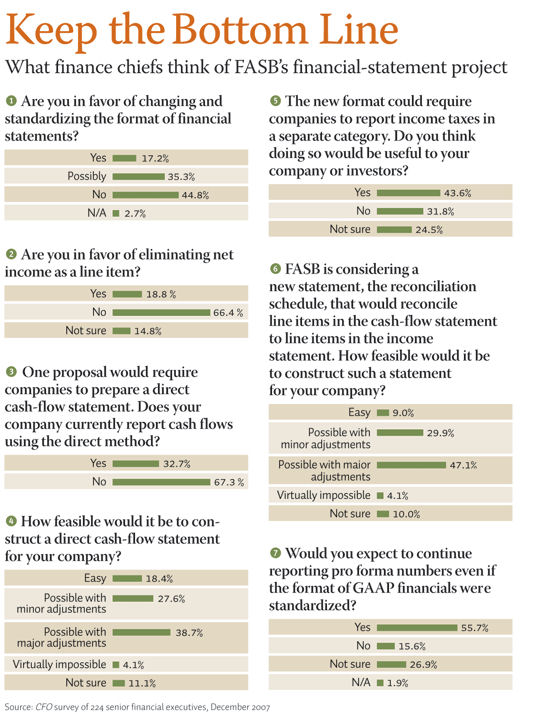

I like this paper. Table 3 could be improved by adding bottom line net earnings

before and after remeasurement.

The paper does not provide all the answers, but it is well written in terms

of history up to this point in time and alternative directions for

consideration.

No Bottom Line

Question

Is a major overhaul of accounting standards on the way?

Hint

There may no longer be the tried and untrusted earnings per share number to

report!

Comment

It would be interesting to see a documentation of the academic research, if any,

that the FASB relied upon to commence this blockbuster initiative. I recommend

that some astute researcher commence to probe into the thinking behind this

proposal.

"Profit as We Know It Could Be Lost With New Accounting

Statements," by David Reilly, The Wall Street Journal, May 12, 2007; Page

A1 ---

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB117893520139500814.html?mod=DAT

Pretty soon the bottom line may not be, well, the

bottom line.

In coming months, accounting-rule makers are

planning to unveil a draft plan to rework financial statements, the bedrock

data that millions of investors use every day when deciding whether to buy

or sell stocks, bonds and other financial instruments. One possible result:

the elimination of what today is known as net income or net profit, the

bottom-line figure showing what is left after expenses have been met and

taxes paid.

It is the item many investors look to as a key

gauge of corporate performance and one measure used to determine executive

compensation. In its place, investors might find a number of profit figures

that correspond to different corporate activities such as business

operations, financing and investing.

Another possible radical change in the works:

assets and liabilities may no longer be separate categories on the balance

sheet, or fall to the left and right side in the classic format taught in

introductory accounting classes.

ACCOUNTING OVERHAUL

Get a glimpse of what new financial statements

could look like, according to an early draft recently provided by the

Financial Accounting Standards Board to one of its advisory groups. The

overhaul could mark one of the most drastic changes to accounting and

financial reporting since the start of the Industrial Revolution in the 19th

century, when companies began publishing financial information as they

sought outside capital. The move is being undertaken by accounting-rule

makers in the U.S. and internationally, and ultimately could affect

companies and investors around the world.

The project is aimed at providing investors with

more telling information and has come about as rule makers work to one day

come up with a common, global set of accounting standards. If adopted, the

changes will likely force every accounting textbook to be rewritten and

anyone who uses accounting -- from clerks to chief executives -- to relearn

how to compile and analyze information that shows what is happening in a

business.

This is likely to come as a shock, even if many

investors and executives acknowledge that net income has flaws. "If there

was no bottom line, I'd want to have a sense of what other indicators I

ought to be looking at to get a sense of the comprehensive health of the

company," says Katrina Presti, a part-time independent health-care

contractor and stay-at-home mom who is part of a 12-woman investment club in

Pueblo, Colo. "Net income might be a false indicator, but what would I look

at if it goes away?"

The effort to redo financial statements reflects

changes in who uses them and for what purposes. Financial statements were

originally crafted with bankers and lenders in mind. Their biggest question:

Is the business solvent and what's left if it fails? Stock investors care

more about a business's current and future profits, so the net-income line

takes on added significance for them.

Indeed, that single profit number, particularly

when it is divided by the number of shares outstanding, provides the most

popular measure of a company's valuation: the price-to-earnings ratio. A

company that trades at $10 a share, and which has net profit of $1 a share,

has a P/E of 10.

But giving that much power to one number has long

been a recipe for fraud and stock-market excesses. Many major accounting

scandals earlier this decade centered on manipulation of net income. The

stock-market bubble of the 1990s was largely based on investors' assumption

that net profit for stocks would grow rapidly for years to come. And the

game of beating a quarterly earnings number became a distraction or worse

for companies' managers and investors. Obviously it isn't known whether the

new format would cut down on attempts to game the numbers, but companies

would have to give a more detailed breakdown of what is going on.

The goal of the accounting-rule makers is to better

reflect how businesses are actually run and divert attention from the one

number. "I know the world likes single bottom-line numbers and all of that,

but complicated businesses are hard to translate into just one number," says

Robert Herz, chairman of the Financial Accounting Standards Board, the U.S.

rule-making body that is one of several groups working on the changes.

At the same time, public companies today are more

global than local, and as likely to be involved in services or lines of

business that involve intellectual property such as software rather than the